taking things seriously

on Timothée Chalamet, Brian Eno, Hayao Miyazaki

There are many trailheads to meaning, but I believe one route is giving yourself the permission to take what you care about seriously. No matter how small. But first, you need to parse what matters to you and admit that it matters.

Desire is embarrassing. Admitting that you want to improve on some measure of subjective quality or taste means admitting that you might fail to meet it. Rupturing your own standard is the necessary price of pursuit.

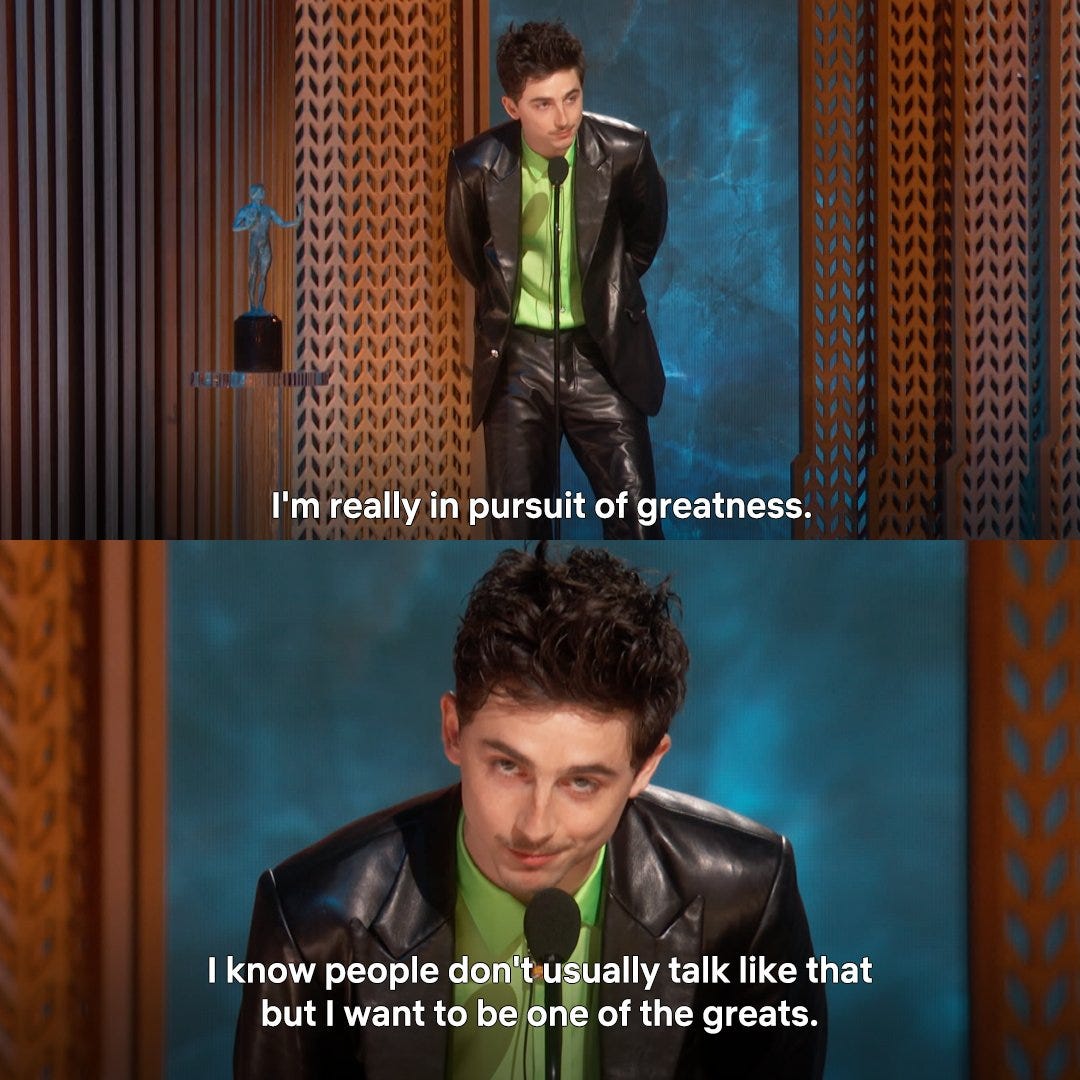

Perhaps that’s why many found Timothée Chalamet’s SAG acceptance speech powerful and refreshing, as simple as it was. “I know we’re in a subjective business,” Chalamet addressed the audience, “but the truth is, I’m really in pursuit of greatness.” He went on to say, “I’m inspired by the greats…I’m as inspired by Daniel Day-Lewis, Marlon Brando, and Viola Davis as I am by Michael Jordan, Michael Phelps, and I want to be up there”

Chalamet’s point about greatness, I think, is a wider point about seriousness. Or that seriousness (upstream discipline and tenacity), is a pre-requisite to greatness. You witness it through his acting. The remarkable intensity with which he portrays Elio in Call Me By Your Name, the petulance of a young boy; and his transformation at the precipice of desire.

After you see it once, you’ll be able to recognize this unspoken quality immediately. When you meet someone with devotion and care for their craft, they have thinner barriers between their soul and the external world. Their soul shines lightly on the surface of their being.

A while back, I booked a last minute solo movie in the Mission. In the velvety darkness of the Roxie theatre I watched Eno, Huswit’s documentary on the legendary musician Brian Eno. In the documentary, Eno talked about how he visualizes music as a landscape: There’s the floor. The shrubbery. A sky. And it takes a long time for that landscape to adhere to itself. I’d never thought about music that way! That’s the promise of depth. You get more scaffolding around language, a deeper and richer vocabulary, to describe how you feel.

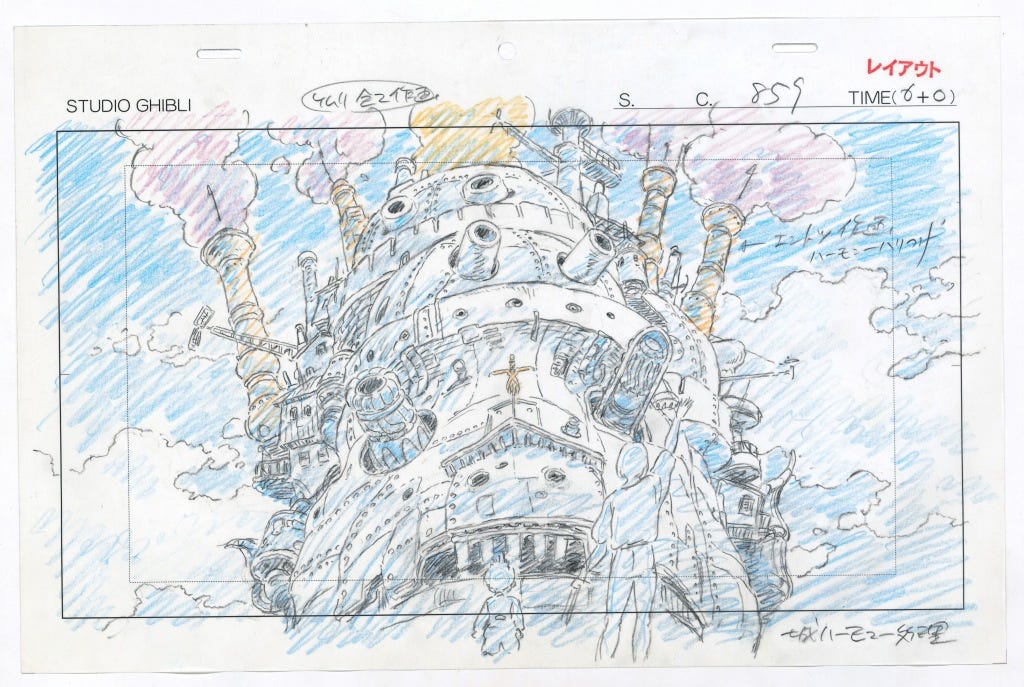

At the same theatre, my friends and I watched Boy and The Heron. What is palpable when one watches a Miyazaki film is the immense care that underwrites each frame. How does it induce such immersion and mesmerism?

Miyazaki changed the conception of what unbelievable texture of fantasy world could be created. Even the food is somehow unbearably delectable. The amber yolked eggs in Howl’s Moving Castle crackle on a hot pan, served fresh with thick slabs of bacon. The gardens and forests are lush, emerald green, dense. Luminescent doors open and close. Miyazaki captures our yearning for the lost world, brings the innocence of childhood wonder to an adult audience. Just look at how lovingly rendered these scenes are:

Here’s what Miyazaki writes in his memoir Starting Point, about the first thirty years of his career:

To endure something is obviously exhausting and agonizing. But at the same time, you must also continue to hold what you regard as important close to your heart and to nurture it. Should you ever relinquish what you truly hold dear, the only path left to you will be that of a pencil-pusher — the type of animator whose sense of self-worth is determined by the numerical amount of their earnings, or who cycles between joy and despair over the high or low rating his work receives.

Beauty is effort. In a rare interview with the animator, Margaret Talbot described Miyazaki as a “workaholic,” and “detail oriented to the point of obsession.” He once travelled to Portugal just to look at one painting by Hieronymus Bosch that haunted him, and he sent the color designer for his films, all the way to Alsace, France to scout for color hues. He rejected the common method of computer animation for meticulously drawing frame by frame by hand.

What we can learn from great craftsmen — be it an animator, actor, writer, designer, etc, is that seriousness matters. You can’t be too precious for maniacal levels of exertion. Effort is monstrous and ugly, but is also the source of everything beautiful in this world.

When I say seriousness I don’t mean rigidity but a deep engagement with life and creation. I believe caring deeply about something lastingly alters your cognition. Sit in lectures on things you never learned in school. Research and adjust every ingredient in the recipe in an attempt to get to the perfect flavor and texture. Build a rose garden. Teach yourself how to build something from scratch; not to achieve perfection, but to be closer to the foundational fabric of the act of making itself. Own your own heat signature. Your indelible effortful mark on the world, a little imprint in the clay.

I’ve accepted I am constitutionally incapable of not caring. My constant wrangling used to be a source of distress, but now I think this inclination is precisely what leads a person into a them-shaped life. I’m more afraid of dispassion than I am of labor. I’m more afraid of apathy than I am of effort made painfully visible. Taking things seriously is deeply human. It’s a sort of special intimacy when you witness someone trying something, anything, in earnest. You either get me, or you don’t.

PS: Thank you for reading - if you feel inclined; please like or share this post. Starting from Nix is a labor of love. Your support helps me curate more posts and reach more readers.

PPS: I do want to write more about Miyazaki - he’s had a pretty fundamental effect on the way I think. I am planning to do more art/culture commentary this year :)

Related, you might like my essay on obsession

On music

Justine and I are making yet another collaborative playlist for the new year themed broadly around relishing the small branches and tributaries of life. Here are some of the songs featured (such range haha):

Best Guess by Lucy Dacus (and Ankles is so good too)

On books

I finished Appetites by Caroline Knapp (thanks B for the rec!) Don’t judge the book by its cover. It is a pretty incredibly precise articulation of female desire/appetite/hunger. In this case, Knapp discusses it from the lens of a warped relationship with food and the female body. I wish there was more on the other sorts of appetites e.g., impulse shopping for example, or what she calls ‘desire' substitution: replacing a desire for one thing with another.

I started reading My Roman Year by André Aciman, and The Suicides by Antonio Di Benedetto. I also finished In Love by Alfred Hayes and am nibbling my way through Oceanic by Greg Egan.

Some incredible quotes here from Appetites:

The primary underlying striving among many women is the appetite for appetite. A longing to feel secure and safe enough to name one's true appetites, and worthy and powerful enough to have them satisfied.

The question of appetite, and specifically, what happens to female appetite when it is submerged and rerouted. Female appetite moves in guilty, circuitous ways.

Where are the lines between satisfaction and excess, between restraint and indulgence, between pleasure and self destruction?"

We seemed to inhabit a realm of essential sparseness, sensuality and strong emotion not completely absent, but muzzled and kept leashed in the yard… wanting is a frightening thing, especially when you lack models for it, or permission or a sense that your own desires are good, valid, and satiable"

and one extended excerpt from In Love:

I really didn’t have a good vice. Liquor in moderate quantities. Love on the installment plan. Wouldn’t it be nice if I could really cultivate some impressive vice? Some excessive cruelty or some astonishing sacrifice. But not even that. Instead, we complain in small voices. Complain we’ve married the wrong girl, taken the wrong job, lived the wrong life.

And what pitiful attempts we make at cures: we raise vegetables in ridiculous gardens, we apply for memberships in athletic clubs, we promise ourselves to read again all the important books we’ve neglected. We think that what we want is a simpler life, and a more active, a more eternal one, and every Wednesday we diligently attend the square dances at the local schoolhouse imagining that a Virginia reel is the way back into a friendly community, and that denims and a checked shirt will restore communication with the stranger who lives next door.

The only thing we haven’t lost, I thought, is the ability to suffer. We’re fine at suffering. But it’s such a noiseless suffering. We never disturb the neighbors with it. We collapse, but we collapse in the most disciplined way. That’s us. That’s certainly us. The disciplined collapsers.

…

Your only vice, I thought, is yourself. The worst of all. The really incurable one.

Really great! Your comment that expressing your desire is vulnerable reminded me of how I also find that being positive feels vulnerable in a similar way. In social situations it's so much easier to get people to agree with you and to "fit in" if you complain about something, but I think that displays of positivity are similar to the kind of Chalamet unapologetic pursuit of greatness on a micro scale.

You know, I don't get how people don't have a thing. Every so often I'll be going about my life, and then I get reminded that someone doesn't have a thing. And I guess to some people it doesn't come naturally, but I've always had a thing, and when I didn't I was busy looking for one.

My thing is how I spend my time, it gives me goals, it gets me outside, it starts conversations, it brings meaning to my life, and as you said, it's something to take seriously.

I love having a thing I can go all in on, I don't know how people live without one.